Recently, I was invited to speak at an event honoring the life and work of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. I am moved by so many of his speeches, but one quote in particular captures the essence of our equity work at the Women’s Bureau, “Whatever affects one directly, affects all indirectly. I can never be what I ought to be until you are what you ought to be.”

This year’s National African American History Month theme is “Black Family: Representation, Identity and Diversity.” As we take time to celebrate the diversity of Black families and reflect on the remarkable achievements and contributions of generations of African Americans in the United States, we must also recognize this is a difficult time for many.

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Black men and women are two times more likely than their white counterparts to experience the loss of a loved one and almost three times more likely to know someone who has been hospitalized from COVID-19.

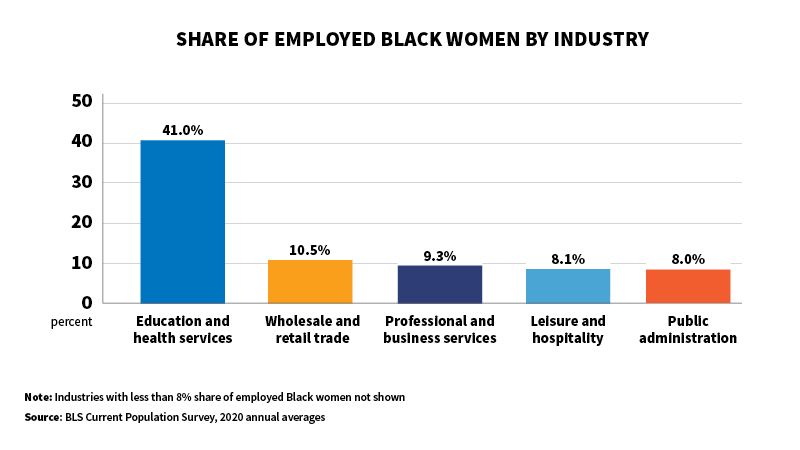

While Black women historically experience the highest labor force participation among women and are more likely to hold multiple jobs than other women or men, throughout the pandemic, Black women have endured the highest unemployment rates. More than half of employed Black women worked in industries hit the hardest by COVID-19.

Plain text chart

In 2020, Black women who were full-time wage earners had median usual weekly earnings of $764, or only 68.8 percent of the $1,110 median usual weekly earnings of white men. This is important to note since 52.3 percent of Black mothers are raising children on their own: Black working mothers’ earnings are essential for the economic security of Black families.

The Women’s Bureau has always been at the forefront of advocating for working women, including supporting racial equity and inclusion in the workplace through our initiatives and research. This work goes as far back as 1922, when we published a detailed statistical report that revealed the working conditions for Black women during that time.

We’ve also been at the center of the push for working women’s rights, ensuring that women were included in the Fair Labor Standards Act in 1938; and playing an instrumental role in the Equal Pay Act of 1963, the Pregnancy Discrimination Act of 1978 and the Family and Medical Leave Act of 1993. These policies have advanced women’s employment prospects and working conditions – yet they have also not been sufficient to ensure equity for Black women in the workforce.

Many Black women are essential workers, and are less likely to have remote work flexibilities. This lack of workplace flexibilities is one of the driving forces behind the Women’s Bureau’s work in the area of paid leave and child care. In recent years, we have advocated for racial and gender equity through a combination of grant-making, education and outreach, and other advocacy work focused on these key policy issues.

It is incumbent on us at the Women’s Bureau, and indeed, on all of us, to recognize and remedy the structural and systemic inequities, the implicit bias, and sometimes the unvarnished racism that constrain women of color from reaching their fullest potential in the workplace and in many other arenas. This is one way that we can fulfill the aspiration of this year’s Black History Month.

We encourage you to follow us on Twitter at @WB_DOL as we continue to elevate research regarding these inequities and mount programmatic responses to combat them.

For more information about the Women’s Bureau, please visit www.dol.gov/wb .

Joan Harrigan-Farrelly is the deputy director of the Women’s Bureau at the U.S. Department of Labor.

Share of Employed Black Women by Industry

| Education and health services | 41.0% |

| Wholesale and retail trade | 10.5% |

| Professional and business services | 9.3% |

| Leisure and hospitality | 8.1% |

| Public administration | 8.0% |

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog