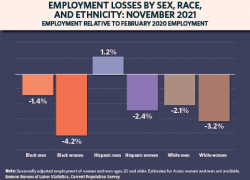

The employment landscape looks much better for workers now than it did a year ago, as the Bureau of Labor Statistics' December jobs report shows. Although the December data predates most Omicron impacts on the labor market, it is encouraging to see that employment continues to increase and the overall unemployment rate has continued to tick down. In December the unemployment rates declined for adult men and adult women (both at 3.6%) – but this was largely driven by changes among white workers as the rates for Black, Asian and Hispanic workers showed little to no change. Things are moving in the right direction, but there is still more to be done to ensure that workers of color – who are often concentrated in low-wage work and are some of the most vulnerable workers – have access to quality jobs and pathways to success.

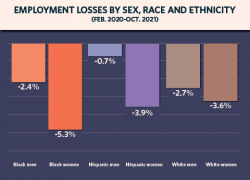

In addition to masking the differences by race and ethnicity, an overemphasis on topline unemployment figures does little to highlight the challenges facing particular occupations and industries. Adult women’s labor force participation increased slightly in December to 57.8% (+0.3%) and remains at pre-pandemic lows not experienced in more than three decades. Women workers are still down 2.1 million jobs, and women’s employment is fully recovered in only four industries: utilities, professional and business services, construction, and transportation and warehousing. And it is worth noting that three of these four industries employed relatively few women before the pandemic – utilities (19.9% of employed workers were women in 2019), construction (10.3%), and transportation and warehousing (24.8%) – making the recovery back to the baseline even less meaningful in relation to women’s overall employment.

While women have made gains in non-traditional industries (defined as those with less than 25% women), many traditionally feminized sectors continue to have significantly fewer workers compared to pre-pandemic numbers. Some of this, such as the decline in jobs in the leisure and hospitality sector, may be due to decreased demand and closed businesses. However, other traditionally women-dominated industries are primarily composed of essential jobs performing labor that provide a foundation necessary for the economy to function. The care sector is a prime example of this phenomenon. As we have seen throughout the pandemic, when care infrastructure – whether for children, people with disabilities or older adults – crumbles, the rest of the nation falters as well. And given cultural expectations around gender roles and caregiving responsibilities within families, it is employed women who tend to carry the heaviest burden.

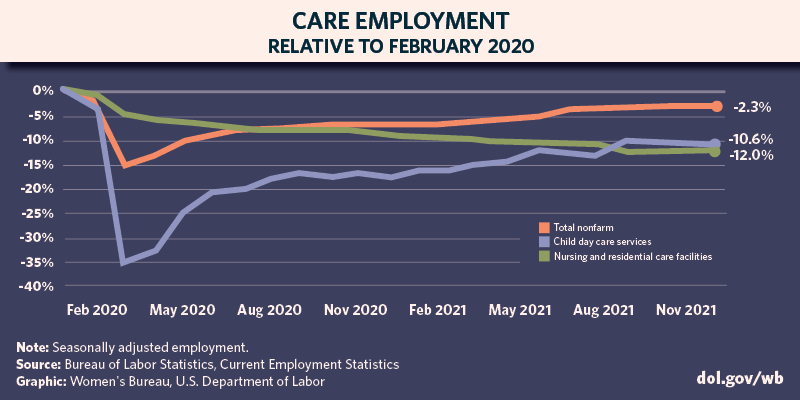

What then, should be done about continued job losses in the care sector? As we have previously covered in this blog series, while the childcare sector has recovered from the significant employment declines experienced in March 2020, 1 in 10 childcare jobs are still “missing” relative to February 2020. Nursing and residential care facilities have fared even worse, with 12% lower employment compared to pre-pandemic. These are industries where the overwhelming majority of workers are women, and provide a service that is vital to the continued employment of women (and men) across the entire economy – not to mention their great importance to the health and wellbeing of the nation.

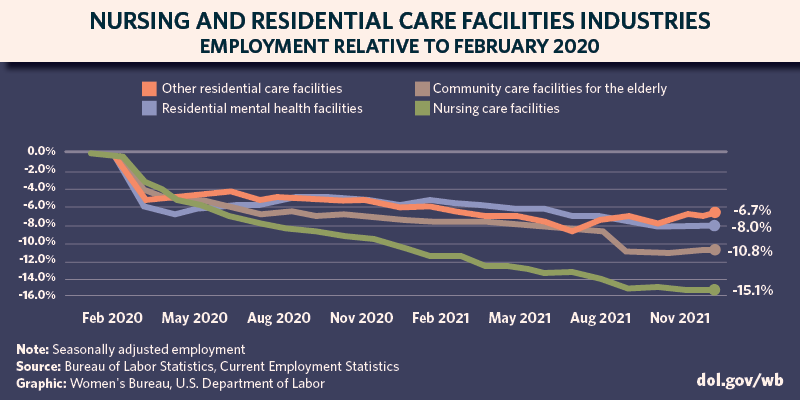

While there are problems across the industry, these jobs losses are especially concentrated in nursing care facilities, which in December 2021 had 240,000 fewer employed workers compared to February 2020. This has tremendous implications for the women who formerly held these jobs, some of whom may have transitioned to other industries but many of whom are likely to be unemployed or pushed out of the labor market. It also should serve as a wakeup call to the rest of the nation, as every one of us has the potential to need access to nursing or residential care facilities for ourselves or our loved ones.

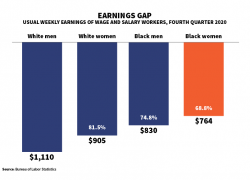

Part of the problem is that these are jobs that have historically offered low wages and few benefits, despite the essential nature of the work. The median hourly wage across nursing and residential care facilities is only $15.16, which is $32,000 a year. Wages are even lower for home health and personal care aides, and nursing assistants, orderlies, and psychiatric aides who make up 4 in 10 workers in the industry; their median hourly wage is only $13.90, or $29,000 a year. This is difficult and important work, but the longstanding lack of investment to support and retain such a vital workforce is having a negative impact on the care infrastructure in the United States.

As the Department of Labor and the Biden administration have repeatedly noted, the economy cannot fully recover if women are left behind. And there cannot be an equitable recovery without addressing the cracks in the nation’s caregiving infrastructure. We must invest in this essential workforce through education, training, increasing wages and enforcement of existing protections and labor standards.

Janelle Jones is the department’s chief economist. Sarah Jane Glynn is a senior advisor in the Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

EDITOR’S NOTE: This blog has been updated. It originally stated that employment in nursing and residential care facilities was 14.2% lower than pre-pandemic levels. This was corrected to 12.0%. The charts have also been updated to reflect corrected employment change for nursing and residential care facilities, nursing care facilities, residential mental health facilities, community care facilities for the elderly, other residential care facilities.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog