This past December, Vice President Kamala Harris launched the first Maternal Health Day of Action and announced a White House call to action to reduce maternal mortality and morbidity rates in the United States. Vice President Harris described it as a crisis for Black mothers and stressed the urgency of “pursuing systemic policies that provide comprehensive, holistic maternal health care … free from bias and discrimination.”

Indeed, the U.S. has among the highest maternal mortality rates in the developed world, and much of these deaths – 60%, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention – are preventable. And even within this context, the likelihood of dying from a pregnancy-related cause is 2.5 times higher for a Black woman in this country than for a white woman. In 2019, the maternal mortality rate for non-Hispanic Black women was 44.0 deaths per 100,000 live births, compared with 17.9 deaths among white women.

Why are Black maternal deaths occurring at such alarmingly high rates? One factor is implicit bias within the health system and among some health practitioners. From lack of access to quality care facilities to subpar treatment at the hands of providers, the legacy of racism in America continues to negatively affect Black health outcomes.

In a recent study, the National Institutes of Health found that healthcare providers were less likely to identify pain in the facial expressions of Black faces than on the countenances of non-Black ones. Because they couldn’t see it, they were less likely to believe a Black patient was experiencing severe discomfort or acute pain. This research is echoed in the voices of many Black mothers who recounted stories of being devalued and disrespected by medical providers during pregnancy and childbirth.

Sadly, despite these increasingly common narratives about maternal deaths, the U.S. health care system has been slow to recognize the role of implicit bias and systemic racism in poor health outcomes for Black women, and especially the role it plays in their higher rates of maternal death. It’s telling that this past December, an illustration of a Black baby in utero developed by a Nigerian medical student went viral because of the novelty of the image, with many respondents noting the rarity of darker skin tones in medical illustrations. Representation matters, and the absence of it, in textbooks and elsewhere, has disparate, and sometimes disastrous, consequences.

Medical and academic institutions are examining ways to tackle this crisis. Florida Atlantic University’s Charles E. Schmidt College of Medicine has revised its curriculum to incorporate training on the impact of implicit bias in medicine: “Medical students start learning about racism in health care during their first year, and as they go, they also learn how to communicate with patients from various cultures and backgrounds.” At the state level, Michigan and California have made implicit bias training a requirement for healthcare provider licensure. The National Association of Nurse Practitioners in Women’s Health has developed an action plan to assess their current policies and practices and determine the gaps that exist and the steps they can take to combat bias and discrimination in patient care.

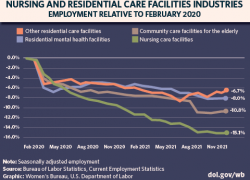

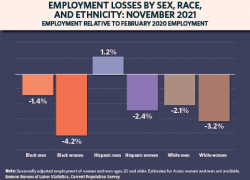

Beyond the obvious impact on their physical, mental and emotional health, Black women may also face the devastating effect of these experiences on their financial well-being. The pregnancy complications resulting from racially motivated differences in treatment protocols may lengthen a woman’s recovery time, which translates into extended, likely unpaid, leave from work. For those without the employment flexibility to return to their jobs after a prolonged absence, adverse health outcomes may lead to indefinite departures from the workforce.

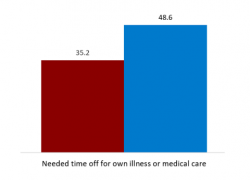

Unfortunately, Black women face a unique double-bind of racialized medical mistreatment and the lack of paid leave that would allow them to recover physically from a medical ordeal without enduring long-term financial repercussions. In fact, Black women are statistically among the most likely to need leave but not take it, even when their own health is at stake. Implicit bias and the lack of a national paid leave program, including parental leave, is a real hardship for many and an obstacle to employment and economic security. For the countless women with told and untold stories of trauma, it is imperative that we both acknowledge and amplify Black women’s voices in advocating for their health, and in doing so, rewrite the narratives around Black maternal health.

Learn more about the work of the Women’s Bureau, including employment protections for workers who are pregnant or nursing.

Joan Harrigan-Farrelly is the deputy director of the Women’s Bureau. Follow the bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog