At the Department of Labor, we’re committed to advancing equity across all the programs and populations we support, including our efforts to increase awareness of and opportunities in apprenticeship — a proven industry-driven career pathway where employers can develop their future workforce and workers can get critical experience through paid and credentialed programs.

Though less common in the U.S. than in Europe, U.S. apprenticeship participation is on the rise. In fiscal year 2020 alone, 3,143 new programs were established, representing a 73% increase from 2009, and the number of active Registered Apprentices grew by 51% in the same period. And these programs are incredibly successful: 92% of apprentices retain employment after completing a Registered Apprenticeship and earn an average starting salary of $72,000.

Though apprenticeships have a proven track record of producing strong results for both employers and workers, we still have a long way to go toward advancing equity in apprenticeship participation. In this equity snapshot, we explore what data we have and what we still need to know to ensure apprenticeship programs are equitably serving all populations. Here are some of our key findings:

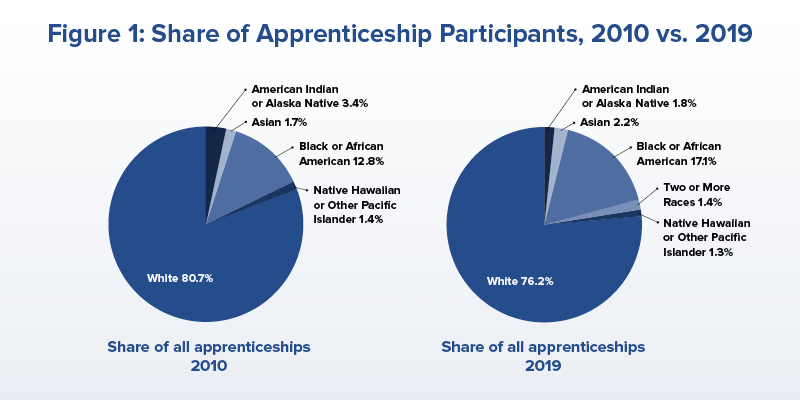

Though most apprentices are white, programs have become more diverse over time

According to demographic data provided by 686,000 apprentices between 2010 and 2019, 77.5% identified as white, 15.3% as Black, 2.9% American Indian/Alaska Native, 2.1% Asian, 1.6% Native Hawaiian/Other Pacific Islander, and 0.5% as multi-racial. With regard to ethnicity, 567,000 apprentices provided information with 18.3% identifying as Hispanic.

But as Figure 1 shows, apprentices have become more diverse over time. This suggests that efforts to boost participation and equity are working — but there’s still more work to be done.

Figure 1. Share of Apprenticeship Participants 2010 vs. 2019 (plain text)

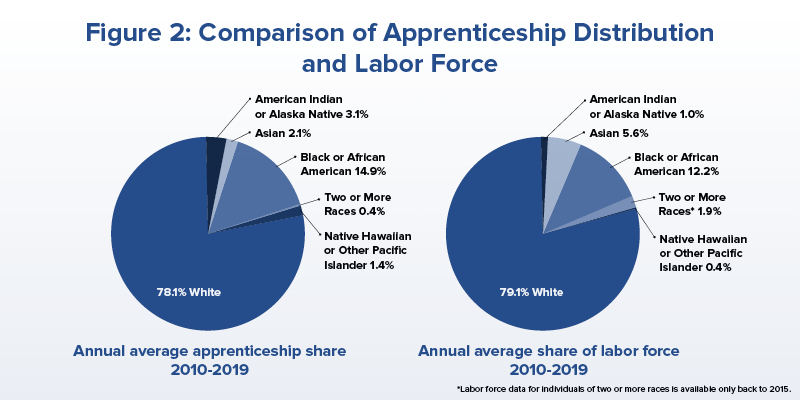

For many racial groups, apprentice representation was higher than overall labor force participation

When comparing apprenticeship participation to the annual average share of labor force participation across all racial groups (Figure 2), we found Black apprentice representation was higher than their labor force representation in 17 industries, and American Indian or Alaska Native apprentices and Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islanders outpaced average representation in 18 industries. This includes construction apprentices, where racial group participation rates mirrored the civilian workforce.

Figure 2. Comparison of Apprenticeship Distribution and Labor Force (plain text)

However, representation of Asian apprentices and apprentices of two or more races fall well below their labor force share

Though some apprentice groups outpaced their peers in the general labor force, this was not the case for Asian apprentices. Whether these issues are structural we aren’t able to address, but we did identify two important issues to note: First, the grouping of Asian sub-groups into a single category may mask additional inequities among these various sub-groups. Second, there are possible identification issues associated with apprentices of two or more races, since survey respondents may self-select into a single racial group without being made aware of the multi-racial category — both of which should be addressed by follow-up surveys to correct and update the data.

Hispanic representation among apprentices is on the rise

Apprentices identifying as Hispanic represented 18.3% of all apprentices from 2010-2019, with an average annual proportion of 15.5%. Hispanic representation among apprentices has been increasing between 2010 and 2019, with the largest jump in representation in 2017 from 14.4 to 22.4%. The overall labor force participation of Hispanics during this time was 16.3%, demonstrating that that though Hispanics hare overrepresented in Registered Apprenticeship programs, they have historically been underrepresented in the labor force overall.

Black apprentices are less likely to complete apprenticeship programs than their white peers

From an equity standpoint, there should be no significant difference in apprenticeship completion rates for individuals of various racial groups or by gender, but our data indicated that this is not the case. While completion rates are below 35% for all racial groups, which speak to the general difficulty of apprenticeships, completion rates for White apprentices reached 33% but only 24% for Black apprentices. Asian apprentices are the only other group to eclipse 30% completion, which suggests that there are factors in play that are negatively affecting completion equity.

Women make up only a small portion of apprentices

Historically, women have not been well represented in apprenticeship programs or in construction industries (where many apprenticeships exist) in general. Between 2010 and 2019, women accounted for an average of 8.5% of apprentices, and only 3.5% of construction apprentices. One study indicated that difficulties securing childcare and lack of pay for classroom instruction were significant barriers to participation and completion of apprenticeship programs – a common narrative for not only apprenticeships, but labor force participation in general.

Additional data is necessary to conduct a full equity analysis

Though our analysis yielded some helpful insights, we uncovered gaps in available data, making a full analysis of apprenticeship equity difficult. For example, we are only able to collect demographic information from program participants and not from applications, and the percentage of apprentices who did not provide demographic information recently jumped from 0 to 10 percent, leaving us with an incomplete picture of the full apprenticeship landscape.

Additionally, as mentioned above, our existing data can’t tell us which Asian and Hispanic sub-groups apprentices identify as, which is necessary to identify and address systemic issues facing these groups. And finally, racial groups are not uniformly distributed across the United States, meaning that we should account for geographic concentrations of various populations to get a better sense of apprenticeship accessibility and labor mobility.

These are just a few examples of what we know (and what we don’t) when it comes to assessing equity across apprenticeship programs. We can’t address what we don’t measure and improving the collection and quality of our data will help us better identify where we are making progress and where we need to improve — in our apprenticeship programs and beyond.

Read our full Apprenticeship Equity Snapshot Memo here.

Janelle Jones is the chief economist, Alexander Hertel-Fernandez is the deputy assistant secretary for research and evaluation, and Christopher DeCarlo is an economist at the U.S. Department of Labor.

Figure 1. Share of Apprenticeship Participants 2010 vs. 2019

| Racial Group | Share of All Apprenticeships 2010 | Share of All Apprenticeships 2019 | Percent Change in Apprenticeship Share |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.4% | 1.8% | -46.3% |

| Asian | 1.7% | 2.2% | 27.9% |

| Black or African American | 12.8% | 17.1% | 33.3% |

| Two or More Races | 0.0% | 1.4% | 3248.1% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1.4% | 1.3% | -6.4% |

| White | 80.7% | 76.2% | -5.6% |

Figure 2. Comparison of Apprenticeship Distribution and Labor Force

| Racial Group | Annual Average Apprenticeship Share 2010-2019 |

Annual Average Share of Labor Force 2010-2019 |

Change in Share of Labor Force 2010-2019 |

| American Indian or Alaska Native | 3.1% | 1.0% | 43.8% |

| Asian | 2.1% | 5.6% | 35.8% |

| Black or African American | 14.9% | 12.2% | 8.7% |

| Two or More Races* | 0.4% | 1.9% | 20.8% |

| Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander | 1.6% | 0.4% | 40.6% |

| White | 78.1% | 79.1% | -4.8% |

(*) Labor force data for individuals of two or more races is available only back to 2015.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog