Most of us know that women are sometimes paid less than their male colleagues. But what you may not know is just how much the difference adds up.

The gender wage gap is a calculation that reflects the fact that, on average, women are paid less than men. In 2020, the latest year with available data, when comparing the median wages of women who worked full-time, year-round to the wages of men who worked full-time, year-round:

All women were paid, on average, 83% of what men were paid. Or put another way, women were paid 83 cents to every dollar paid to men.

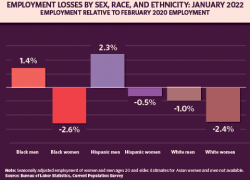

Many women of color were paid even less. For example, Black women were paid 64%, and Hispanic women (of any race) were paid 57% of what white non-Hispanic men were paid.

These figures are calculated by looking at the median wages of all workers who were employed full-time for at least 50 weeks out of the year, so these figures reflect many notable differences between working women and men. These are useful numbers to help identify a distinct pattern of lower pay, but by themselves these figures do little to help us understand why women’s pay is lower.

In 2020, the Women’s Bureau collaborated with the U.S. Census Bureau to conduct what is currently the most comprehensive analysis of the gender wage gap to date. The data shows that the majority of the gap between men and women’s wages cannot be explained through measurable differences between workers, such as age, education, industry or work hours. It is highly likely that at least some of this unmeasured portion is the result of discrimination, but it is impossible to capture exactly in a statistical model.

Of the portion of the wage gap that can be explained, by far the biggest factor is the types of jobs that women are more likely to have than men; and these are jobs that tend to pay less. This industry and occupational segregation – wherein women are overrepresented in certain jobs and industries and underrepresented in others – leads to lower pay for women and contributes to the wage gap for several interrelated reasons.

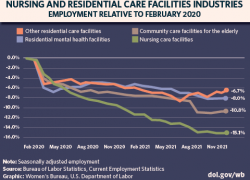

First, the jobs where women are most likely to work pay lower wages overall than jobs with a majority of men. This is especially true of jobs in care work, such as childcare workers, domestic workers, and home health aides, all of which pay below average wages. And while it does not contribute directly to the wage gap, women-dominated jobs also are less likely to include benefits like employer-provided health insurance and retirement plans compared to occupations dominated by men.

Second, even within these female-dominated jobs, women are paid less on average than men in the same job. When comparing more than 300 detailed occupations, there are none where women have an earnings advantage over men, but hundreds where men have significantly higher earnings than women. A new interactive data tool from the Women’s Bureau compares the wage gap by sex, race, ethnicity and occupation group. Regardless of occupation group, women always have lower average earnings than men, and Black and Hispanic women nearly always have the largest wage gaps of any group of women when compared to white non-Hispanic men. For example, as shown in Figure 1, in service occupations Black women are paid only 65% of what white non-Hispanic men are paid, while Hispanic women are paid only 58%.

And third, because women’s labor is so devalued, the average pay for an occupation has been shown to decrease when women start to enter a field in larger numbers. Occupations that employ a larger share of women pay lower wages even after accounting for characteristics of the workers and job, such as education, skills and experience.

Even though differences in the types of jobs men and women hold only explains a part of the wage gap, the total costs are huge. A new Department of Labor report estimates that in 2019 alone, segregation by industry and occupation cost Black women an estimated $39.3 billion, and Hispanic women an estimated $46.7 billion, in lower wages compared to white men.

Efforts to close the gap must address occupational and industrial segregation, in addition to discrimination and other unmeasurable factors that drive down women’s, and especially women of color’s, pay. This will require supporting women entering male-dominated fields, raising wages and job quality across all sectors and especially in women-dominated jobs, and ensuring racial and gender equity in all jobs including in the high growth fields creating the jobs of the future.

Sarah Jane Glynn is a senior advisor with the Women’s Bureau. Diana Boesch is a policy advisor in the Office of the Assistant Secretary for Policy. Follow the Women’s Bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog