On Jan. 15 we celebrate Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.’s birthday to remember his enormous contribution to the struggle to advance the civil rights of tens of millions of Black Americans. But Dr. King’s legacy extends beyond civil rights to human rights, writ large. Among other things, Dr. King understood human rights included recognizing the dignity of work for all people, whatever their race, the economic disparity between capital and labor, and the role labor unions play in trying to reduce that disparity.

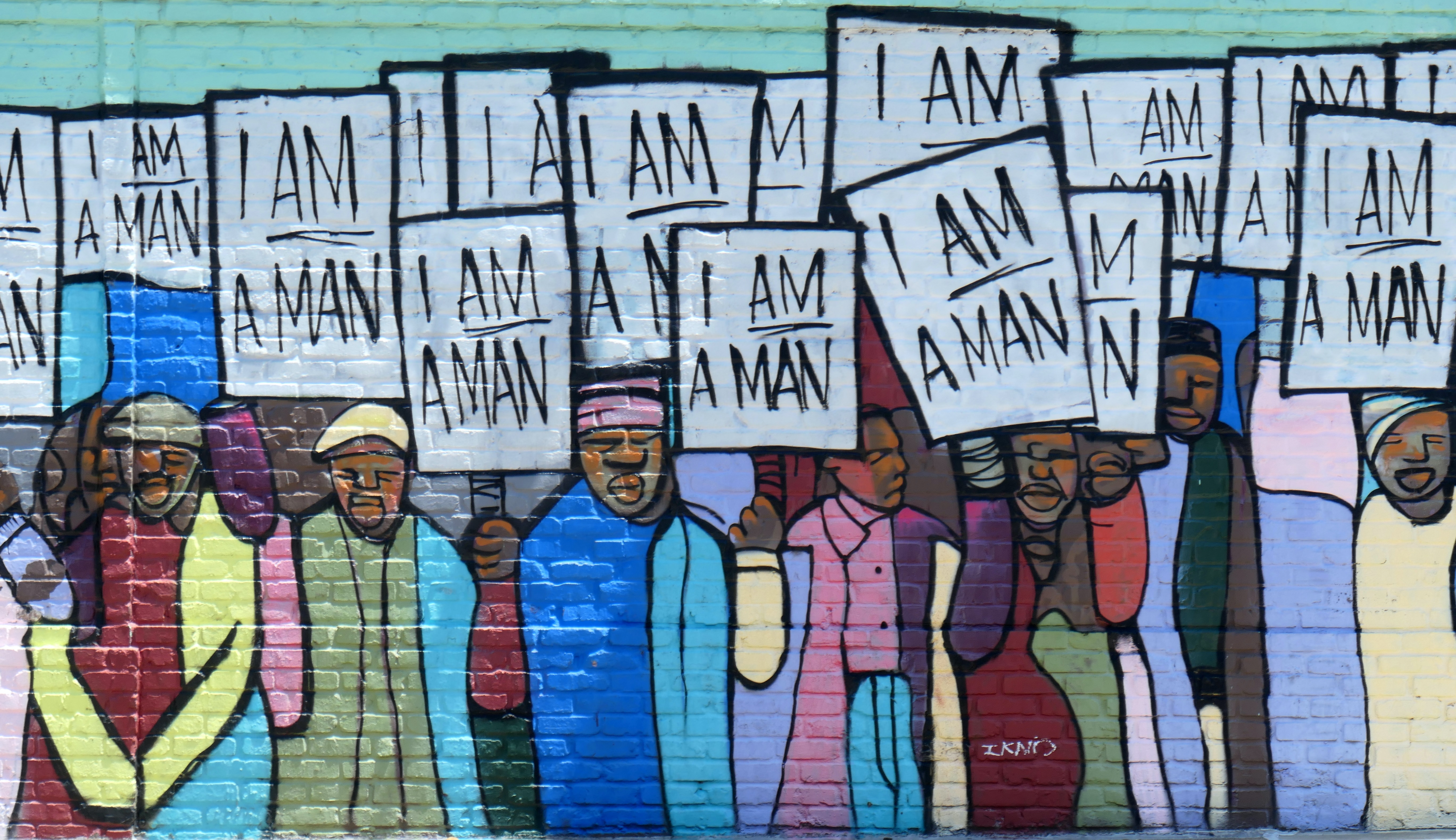

While many Americans know that Dr. King was assassinated in Memphis in April 1968, fewer of us remember why he was there. He was on his third trip to Memphis to support a strike by sanitation workers seeking union recognition from the Memphis Department of Public Works as a vehicle for increasing their wages and improving their working conditions. That strike, with its “I AM A MAN” picket signs, drew a straight line between the workers’ dignity and their legitimate economic aspirations. Those sanitation workers, who today are represented by the Teamsters Local 667, are honored in the Labor Department’s Hall of Honor.

It should have been no surprise to anyone that Dr. King would support both the dignity of work generally and workers who wanted to organize more specifically. As early as 1957, he delivered what is known as his “Street Sweeper Speech,” in which he said:

"What I'm saying to you this morning, my friends, even if it falls your lot to be a street sweeper, go on out and sweep streets like Michelangelo painted pictures; sweep streets like Handel and Beethoven composed music; sweep streets like Shakespeare wrote poetry; sweep streets so well that all the host of heaven and earth will have to pause and say, 'Here lived a great street sweeper who swept his job well.’"

By the 1960s he focused his lens more intensely on the role of unions in advancing workers’ lives. In a 1965 speech to the Illinois AFL-CIO Convention, Dr. King observed that:

"[d]uring the thirties, wages were a secondary issue; to have a job at all was the difference between the agony of starvation and a flicker of life. The nation, now so vigorous, reeled and tottered almost to total collapse. The labor movement was the principal force that transformed misery and despair into hope and progress. Out of its bold struggles, economic and social reform gave birth to unemployment insurance, old age pensions, government relief for the destitute, and above all new wage levels that meant not mere survival, but a tolerable life. The captains of industry did not lead this transformation; they resisted it until they were overcome. When in the thirties the wave of union organization crested over our nation, it carried to secure shores not only itself but the whole society."

A few years earlier in a speech to the AFL-CIO, Dr. King spoke these words, which brought together in plain terms the relationship between civil rights and workers’ rights:

"In our glorious fight for civil rights, we must guard against being fooled by false slogans, such as 'right to work.' It is a law to rob us of our civil rights and job rights. It is supported by Southern segregationists who are trying to keep us from achieving our civil rights and our right of equal job opportunity. Its purpose is to destroy labor unions and the freedom of collective bargaining by which unions have improved wages and working conditions of everyone. Wherever these laws have been passed, wages are lower, job opportunities are fewer and there are no civil rights. We do not intend to let them do this to us. We demand this fraud be stopped. Our weapon is our vote."

While things may have improved since Dr. King spoke those words, we still have a long way to go. The national policy embedded in both the National Labor Relations Act and the Labor-Management Reporting and Disclosure Act, which the Office of Labor-Management Standards enforces, “to protect employees’ rights to organize, choose their own representatives, bargain collectively, and otherwise engage in concerted activities for their mutual aid or protection,” sets the template for that future progress. Dr. King spoke for all workers – regardless of their race, sex or ethnicity – when he hailed the dignity of work and the important role America’s unions have in advancing economic justice. As a nation, we are better off for the time he gave us. The Labor Department honors his legacy every day by advancing workers' rights and promoting equitable job opportunities.

Jeffrey Freund is the director of the Department of Labor’s Office of Labor-Management Standards.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog