My work and the work of my colleagues at the Wage and Hour Division is to protect vulnerable workers from violations of some of their most fundamental workplace rights, like minimum wage, overtime and job-protected leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act.

My work and the work of my colleagues at the Wage and Hour Division is to protect vulnerable workers from violations of some of their most fundamental workplace rights, like minimum wage, overtime and job-protected leave under the Family and Medical Leave Act.

Every day, and especially as I reflect on Black History Month, I draw inspiration from the stories of leaders who helped to improve working conditions for Black workers. One such source of inspiration is the story of the Double V Campaign, which led to improved working conditions for Black workers at the Department of Defense.

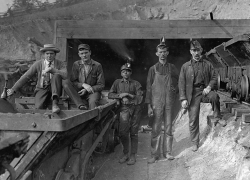

During World War II, while the war effort was creating demand for many workers in the United States, long-held prejudices created barriers to employment for many Black workers.

The Second Great Migration, beginning in 1940, saw the number of Black workers in the defense industry triple. More than 1 million Black workers migrated to the North and West from the South, seeking industrial jobs from defense contractors where the average weekly wages were much higher.

Black workers made invaluable contributions to America’s war effort even as they faced ongoing discrimination in the workplace. For example, Black workers at Chicago’s Metallurgical Laboratory and at facilities in Oak Ridge, Tennessee provided crucial support to projects led by the renowned physicist Robert Oppenheimer that led to the development of the atomic bomb. At the Chicago “Met Lab,” Black scientists like Ernest Wilkins, Jr. and Ralph Gardner-Chavis were vital to the development of the separation of plutonium that made the controlled nuclear reaction possible. Black workers also supported uranium enrichment research at the Oak Ridge lab.

Despite their importance to this work, Black workers faced all sorts of discrimination – from being relegated to menial jobs to being denied security clearances to receiving lower wages than their white colleagues. As the war effort generated millions of jobs, many in urban areas, Black job seekers faced violence and discrimination. Black leaders then met with Eleanor Roosevelt and members of President Franklin Roosevelt’s cabinet, presenting a list of grievances and demanding that discrimination in the defense industry cease. These Black workers’ contributions – and their demands – led to overdue but important change. President Roosevelt issued Executive Order 8802 in June 1941. It stipulated, “There shall be no discrimination in the employment of workers in defense industries and in Government, because of race, creed, color or national origin.”

While the order was groundbreaking, discriminatory practices persisted. In 1942, the Pittsburgh Courier (the largest Black newspaper in the U.S.) published a letter from James G. Thompson, a 26-year-old defense worker, that contrasted the war rhetoric with the treatment of Black workers in the industry. Thompson called for a “double V for victory” sign representing victory at home and abroad. Black workers embraced the Double V campaign, marching in cities across the country and demanding improved working conditions for the millions of Black workers in defense plants. They also demanded an acknowledgement of the contributions and sacrifices of more than 1 million Black men and women serving in the Armed Forces.

Our nation has made progress over the decades, building on the work of these and other advocates to create more just workplaces. Yet the problems of racial discrimination and occupational segregation persist, creating barriers to entry in many industries and jobs for Black workers. The result is that, as one recent study found, 47% of Black workers work in low wage jobs where they earn less than $15 an hour. Low-wage workers are also more likely to suffer from wage theft, such as being deprived of overtime due to misclassification.

Today, Black workers across the country continue to carry on the legacy of the Double V campaign by coming together to demand better working conditions. Last year, for example, due to the courageous collaboration of Black farmworkers and the partnership of the Mississippi Justice Center, we recovered $505,000 for Black farmworkers in the Mississippi Delta whose rights under the worker protections of the H-2A program had been violated. Earlier this month, Acting Secretary Su visited our Wage and Hour Division District Office in Mississippi, and we again heard from Black workers who stood up to denounce the wage theft they experienced.

At the Wage and Hour Division, we know that Black workers deserve better. They deserve good jobs where they can trust that their wages won’t be stolen – and protection from retaliation when they do speak out against violations of their rights. We’re doing our part to help create good jobs and carry on the legacy of the Double V campaign by preventing and addressing wage theft for Black workers across the country.

Frank McGriggs is the Southeast deputy regional administrator for the Department of Labor's Wage and Hour Division. Follow the division on X at @WHD_DOL and on LinkedIn.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog