On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Company on the top floors of the Asch Building, near Washington Square Park in New York City. Many of the workers were women, some as young as 14, and most were immigrants. The fire spread quickly, and workers who rushed to the exits found they had been locked in by their managers – a common practice at the time.

On March 25, 1911, a fire broke out in the Triangle Shirtwaist Company on the top floors of the Asch Building, near Washington Square Park in New York City. Many of the workers were women, some as young as 14, and most were immigrants. The fire spread quickly, and workers who rushed to the exits found they had been locked in by their managers – a common practice at the time.

An estimated 146 workers perished in the fire. Witnesses watched in horror as some jumped from the ninth floor and fell to their deaths. Among the witnesses was future Secretary of Labor Frances Perkins, who carried the memory of the fire throughout her long career advocating for better workplace protections.

At the start of the 20th century, and the close of the second industrial revolution, many American women had found expanded opportunities for employment in a growing textile industry, rapidly transformed through the expansion of machinery and demand. Despite these expanding opportunities, working conditions in these factories were often miserable.

The nation’s labor movement was also in the process of transition, transforming from craft guilds into organizing bodies representing exploited lower skilled factory workers, and these bodies increasingly called for change within the industry. In 1909, 20,000 workers, mostly women, struck in demand for safer working conditions.

Despite the size of the strike, dangerous conditions persisted, as the Triangle fire proved. The tragedy awoke the public to the need for a change in a way that previous efforts had failed to do. With broader support, the ongoing efforts of the labor movement, and the support of Frances Perkins, conditions began to improve.

When President Roosevelt asked her to be the Secretary of Labor, she had already prepared a set of labor policy priorities including a 40-hour work week, Social Security, health insurance, minimum wage, unemployment compensation, workers’ compensation and abolishing child labor.

One hundred and ten years later, we can see echoes of the Triangle tragedy in the COVID-19 pandemic. In the early twentieth century, the U.S. economy benefitted from the labor of young, immigrant workers, often toiling in dangerous and exploitative conditions. The pandemic has revealed the extent to which our economy still relies on the labor of essential workers, many of them female, with limited protections.

Women, especially women of color, are disproportionately represented in public-facing service jobs that have been hard-hit by lack of adequate personal protective equipment and paid leave. The growth of gig and service work, coupled with decreasing union representation for these workers, has left many without the resources to collectively improve their workplaces.

Working women are having to choose between staying safe and supporting their families, between employment and the essential but unpaid work caring for family members. Since February 2020, Black women’s labor force participation rate has declined by 4.2 percentage points, compared to 4.1 percentage points among Hispanic women, and 1.9 percentage points among White women.

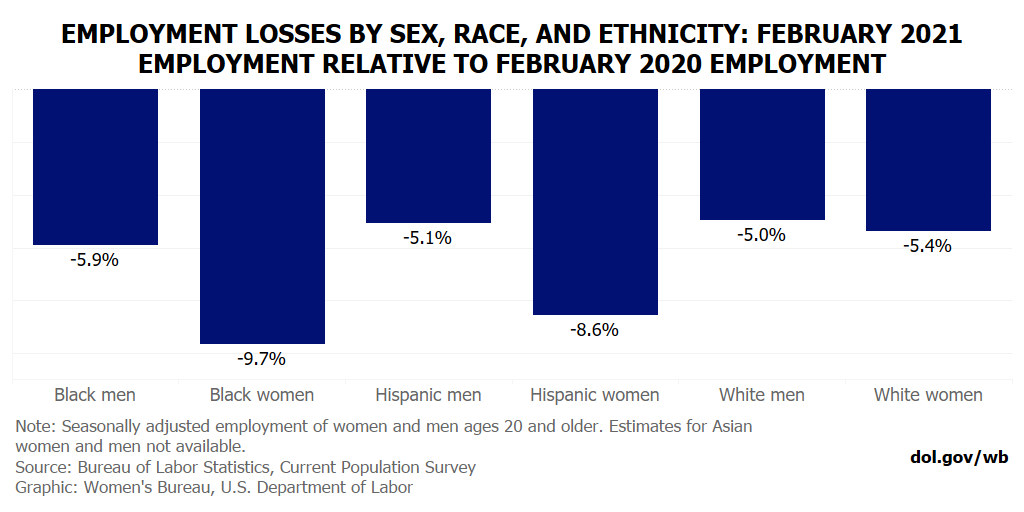

Furthermore, millions of working women, in particular women of color, who make up a large share of service sector jobs that cannot be done remotely, have found themselves unemployed. About 9.7% fewer Black women, 8.6% fewer Hispanic women, and 5.4% fewer White women were employed in February 2021 compared with February 2020. These changes have set women’s labor force participation back about 30 years, and will undoubtedly have a lasting impact on the economic security of these women and their families.

The American Rescue Plan directly addresses many of the challenges and risks faced by workers during the pandemic . Measures include providing direct stimulus payments, expanding unemployment benefits, providing funding to expand access to personal protective equipment, accelerating vaccinations, providing tax credits to businesses that offer emergency paid leave, increasing tax credits to cover the cost of childcare, and much more. These measures will not only help protect essential workers from the virus, but also provide more comprehensive supports for employed and displaced workers alike.

While this legislation has provided much needed aid to working women, opportunities remain to advance women in the workforce. For more than a century, the Department of Labor has led the charge in supporting the American workforce and setting generations upon a path of greater economic security. By pursuing policies that support historically overlooked workers, we can ensure that today’s workers and tomorrow’s will be better protected than the generations that came before.

Analilia Mejia is the deputy director of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Women’s Bureau. Follow the Women's Bureau on Twitter: @WB_DOL.

Employment Losses by Sex, Race and Ethnicity: February 2021 Employment Relative to February 2020 Employment

Black men: -5.9%

Black women: -9.7%

Hispanic men: -5.1%

Hispanic women: -8.6%

White men: -5.0%

White women: -5.4%

Note: Seasonally adjusted employment of women and men ages 20 and older. Estimates for Asian women and men not available.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey

Graphic: Women's Bureau, U.S. Department of Labor

dol.gov/wb

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog