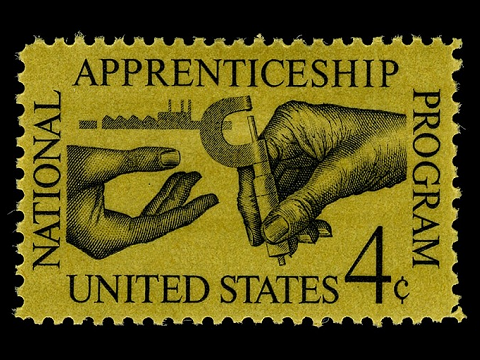

This week is National Apprenticeship week, a great moment to reflect on organized labor’s contribution to apprenticeship programs. It is a complicated history, but in recent years, union-sponsored apprenticeship programs have become an engine for advancing racial and ethnic minorities and women into higher-paid segments of the workforce, and for helping lift all of their apprenticeship graduates into sound middle-class jobs.

For centuries, apprenticing in one form or another has been a vehicle for bringing new workers into skilled trades. From the colonial era to the early 1900s, apprenticeships were largely unstructured and unregulated. In 1917, a coalition of business and labor – fueled by the need for skilled labor to meet the manufacturing demands of World War I – helped secure the passage of the Smith-Hughes Act, which provided federal aid for vocational education. The Smith-Hughes Act laid the groundwork for the subsequent Vocational Education Act of 1963 and, most recently, the Carl D. Perkins Vocational Education Act of 1984. With the help of these federal funds, unions and employers – together and separately – developed training programs on a location-by-location basis.

And in 1937, Congress passed the National Apprenticeship Act, also known as the Fitzgerald Act, which provided authority to establish standards specifying the kinds and quality of training registered apprenticeship programs were to provide, as well as the responsibilities of joint labor-management apprenticeship committees that were to oversee that training. The Fitzgerald Act was the effective starting point for moving the development of apprenticeship programs into the world of collective bargaining.

The motivations in both the employer and union world for expanding apprenticeship programs have not always been pure. For too long, many were thinly disguised efforts by employers to find cheap labor. Others were protectionist measures by skilled craftsmen to restrict entry into their profession, helping to create a pathway for their sons (but not typically their daughters) into their fathers’ crafts.

The complicated history of apprenticeship programs has continued almost to the present day. OLMS’s participation in the investigation of the abuse of the Fiat-Chrysler/UAW Training Fund by both employer and union representatives led to the indictment and conviction of multiple union and employer representatives – and the company itself. These events have led to a restructuring of the industry’s training programs that will better serve auto workers and the industry.

But in recent years, it appears that union-sponsored apprenticeship programs are leading the way to higher pay and greater inclusivity into the skilled trades.

- A study of Pennsylvania apprenticeship programs for the period 2000-2016 by Keystone Research found that while jointly sponsored union-employer apprenticeship programs accounted for 85% of all construction trade apprentices, they accounted for over 90% of apprentices who were women and non-white men. Graduation rates were also higher in joint union-employer programs. For apprentices enrolling between 2000 and 2012, graduation rates for minority male, women and veteran participants were 25% higher than for those in non-union programs. And, overall, starting and completion wage rates were 36% and 60% higher, respectively, for apprentices in joint union-employer programs than in non-union ones.

- A study conducted by the University of California at Berkeley Labor Center for Labor Research and Education found that the share of workers of color entering apprenticeships in the three construction trades responsible for building most of the clean energy power plants in California reached 60% in 2017, compared with 56% for the state’s workforce as a whole. And veterans participated in these programs at a higher rate than in the workforce more broadly.

- North America’s Building Trades Unions are working to create more diverse apprenticeship programs through their comprehensive apprenticeship readiness programs throughout the U.S. These programs provide a gateway for local residents – focusing on women, people of color, and transitioning veterans – to gain access to Building Trades’ registered apprenticeship programs. ARPs are administered by state and local Building Trades Councils and they teach NABTU’s nationally recognized Multi-Craft Core Curriculum.

- Finally, a very recent report by the Illinois Economic Policy Institute on apprenticeship programs focusing on in Illinois, Wisconsin, Minnesota, Oregon, and Iowa in the 10-year period between 2010 and 2020 concluded that diverse racial and ethnic participation in joint union-employer apprenticeship programs compared favorably to the racial and ethnic composition of public universities; participation by the same groups was lower in employer-sponsored programs. It also concluded that graduates of joint union-employer apprenticeship programs earn more, are more likely to have private health insurance coverage and are more likely to have access to pension plans than graduates of employer programs.

More work needs to be done to ensure the growth of quality, equitable programs, and the good news is that more is being done. In February, President Biden rescinded Executive Order 13801 that, during its short life, spurred the growth of sub-standard employer-only apprenticeship programs, and also announced his support for the bipartisan National Apprenticeship Act of 2021.

Recently, the Department of Labor announced a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking seeking public comment on a proposal to eliminate the Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Program, allowing the department to direct its resources toward expanding access to good-paying jobs through Registered Apprenticeships and creating reliable pathways to middle class.

And in September, the Department of Labor appointed 29 leaders from organized labor, industry and the public to the newly revitalized Advisory Committee on Apprenticeships. The committee will help promote greater awareness of the benefits of apprenticeship, foster increased alignment between apprenticeship opportunities and education systems, expand apprenticeship into new industries and occupations, and ensure equity for under-represented populations.

Hopefully – through its work and the ongoing work of researchers in the private and public sector – we will be able to confirm what my personal experience has led me to believe: Apprenticeship programs developed through cooperative labor management relationships are the keys to an equitable path to the middle class.

Jeffrey Freund is the director of the U.S. Department of Labor’s Office of Labor-Management Standards.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog