The unemployment rate dropped to 6.3% in January 2021, according to the latest Employment Situation report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics. Many workers are still in crisis and we know that the latest recession hasn’t affected everyone equally.

In addition to major disparities in health impacts, Black Americans have seen disproportionate economic impacts from the pandemic. Among demographic groups, Black women experienced the steepest drop in labor force participation and have had the slowest job recovery since January 2020. It took until 2018 for Black women’s employment to recover from the Great Recession, and now almost all of those hard-won gains have been erased.

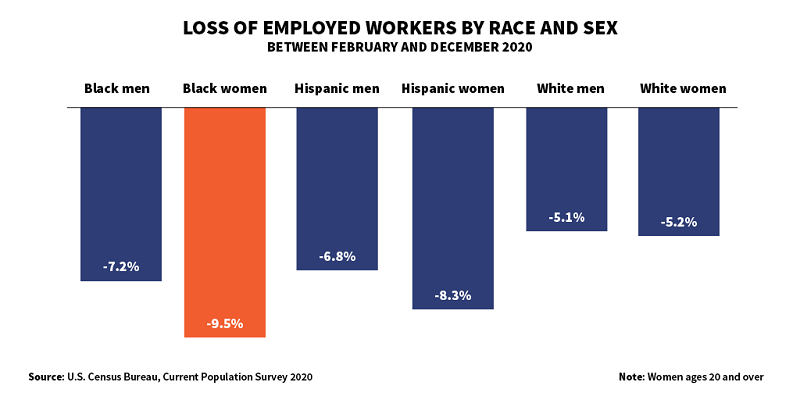

In January 2021, 973,000 fewer Black women were employed than in February 2020, a decrease of 9.5% since the COVID-19 pandemic began. The losses in local and state government and leisure and hospitality have disproportionate impacts on Black women’s employment. Black women are nearly one in four public sector workers, and one in eight leisure and hospitality workers. Half a million Black women have left the labor market since January 2020.

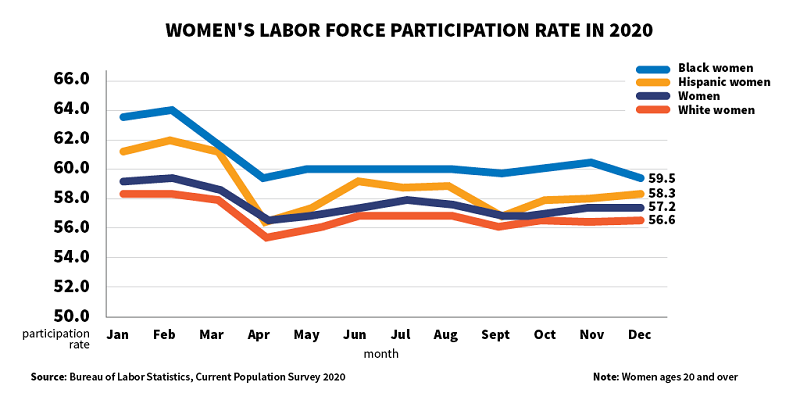

We can also look at labor force participation. Due to historical expectations of work outside the home for Black women, they have always been more tightly attached to the labor market than other women. While Black women have the highest labor participation rate among all adult working women, at the same time their rate dropped the most. It fell by 4 percentage points between January and December 2020, compared with a 2.8 percentage point drop among Hispanic women and 1.7 percentage point drop among white women.

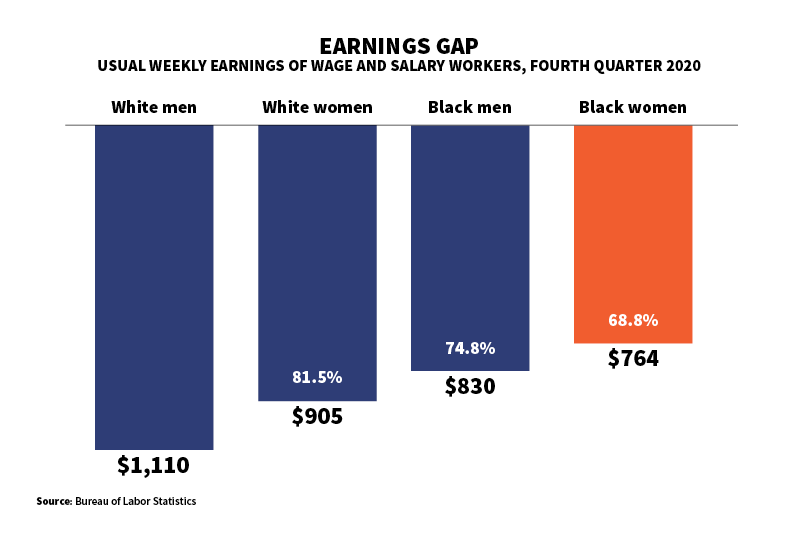

Due to longstanding inequities in education and the labor market, Black women workers are overrepresented in low-paying service sector jobs, which have been slow to rebound as the country still grapples with the virus. The industry that employs the largest number of Black women is education and health services – about 3.9 million Black women worked in this sector in 2020. A number of studies have shown that workers in occupations with lower average earnings were much more likely to be displaced by the pandemic than those with higher average earnings.

The latest data isn’t unusual. The economics of Black Americans have always been worse than what the average statistics suggest. In fact, in every economic recession of the last 50 years, Black women have had higher unemployment rates than white men – and the recovery rates of Black men and women have been slower than that of the white labor force.

We saw this in the aftermath of the Great Recession; while headline numbers touted “recovery,” many Black women – and their families and communities – continued to struggle. No economic recovery can be complete if some communities are left behind.

Centering relief and recovery policies around the needs of Black women and other vulnerable workers will ensure an inclusive economy for everyone. This will mean involving those communities in identifying needs, policy development, solutions and action. It means addressing long-standing history of racial discrimination across our economy – in pay, education, health care, housing and wealth building – and ensuring everyone can access the resources and opportunities they need to thrive. We can course correct one of the worst economic downturns in U.S history for all by deliberately improving the economic outcomes of traditionally marginalized groups. We can’t resort back to business as usual.

During Black History Month, we have an opportunity to honor the Black Americans who helped advance civil rights and racial justice by continuing their work. We honor them – as well as the frontline heroes whose work helped sustain the nation through this pandemic and the many workers who lost their livelihoods through no fault of their own – by building a more inclusive economy where all Americans will benefit from the growth to come.

Editor’s note: If you are unemployed, or need career or training help, visit CareerOneStop.org to connect with local resources.

Janelle Jones is the U.S. Department of Labor’s chief economist.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog