The Bureau of Labor Statistics’ October jobs report contained many positive changes, including strong jobs gains and upward revisions for previous months’ job growth. Women workers appear to have done especially well last month, accounting for more than half (304,000 or 57.2%) of all jobs gains. Adult women’s employment and labor force participation rose, both of which are positive signs that offset each other, leading to the largely unchanged women’s unemployment rate.

Unfortunately, one month’s gains, even when coupled with previous months’ upward revisions, are not enough to fully undo the impact of the pandemic on women’s employment. There are still 2.6 million women missing from work, as the number of employed women is still 3.2% lower than it was in February 2020. By way of comparison, men’s employment is down 2.6%, accounting for 2.1 million men.

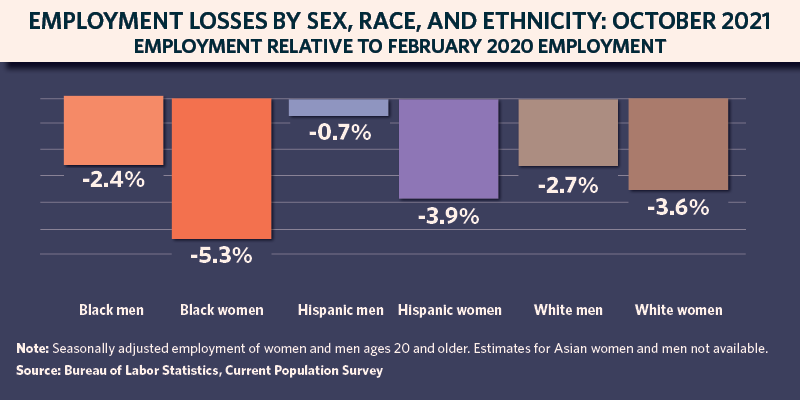

These topline numbers, while important, mask many of the ways that the pandemic’s impact on employment continues to play out differently for different groups of women. Black and Hispanic women’s employment has not recovered as much as white women’s, and employment losses for Black women since the start of the pandemic have been far greater than those experienced by white and Hispanic women.

Employment Losses by Sex, Race and Ethnicity: October 2021 Employment Relative to February 2020 Employment (plain text)

Black women’s unemployment rate fell from 7.3% in September to 7.0% in October – but not because they gained jobs. In fact, over that time period the economy lost 34,000 employed Black women, and a total of 52,000 Black women left the labor force entirely. By way of contrast, white women added 165,000 jobs, and 292,000 white women entered or rejoined the labor force, meaning that they were working or actively searching for a job. Hispanic women of any race added 94,000 jobs, and 114,000 Hispanic women entered or rejoined the labor force. This is not to say that white and Hispanic women are no longer experiencing employment challenges, as their overall employment has not rebounded to pre-pandemic levels (nor has men’s). However, the data does indicate that Black women are having a different experience as the economy recovers, and more needs to be done to support their reentry into the labor force and employment.

Women – women of color specifically, and Black women particularly – have faced additional employment challenges for overlapping reasons. Part of the problem is that the industries hardest hit by the pandemic, such as leisure and hospitality and education and health services, are ones that disproportionately employ women and women of color. As these industries regain jobs (leisure and hospitality added 164,000 jobs, 96,000 of which went to women) we should expect to see women’s employment and labor force participation increase.

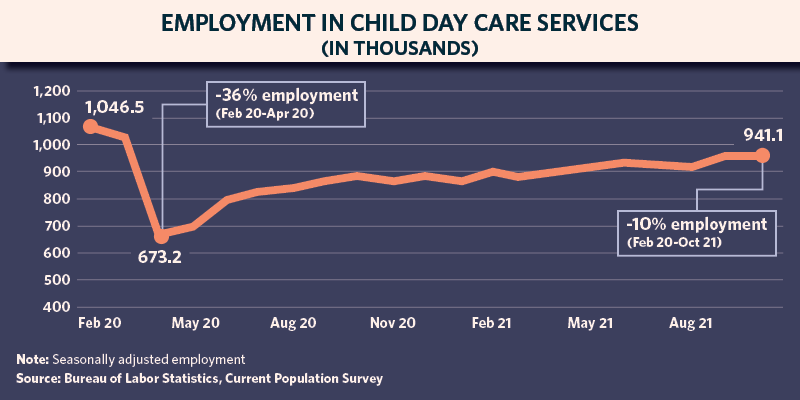

Unfortunately, many women can't reenter the labor force or take a new job due to their caregiving responsibilities. Women are more likely than men to be responsible for family caregiving, whether for children, elders or other family members with needs. One big missing piece of the puzzle for women is child care. Employment is down by 10% in child daycare services since February 2020, with 105,400 fewer workers employed in the industry. This is a double whammy for working women, since when child care is not available mothers of young children cannot work, and because the majority of childcare workers are women – and are especially likely to be women of color.

Employment in Child Day Care Service (plain text)

The economy will not be fully recovered until women – including women of color – can take care of their families and maintain employment. And this will not be possible until care for children is more universally available. While the recent approval of vaccines for children ages 5-11 will likely help to decrease school closures and hopefully provide much needed stability for working parents, rebuilding the childcare sector for younger children is also necessary to enable mothers to work, and to help re-fill the 100,000+ job losses in the industry. The economy can’t work if women don’t work, and women can’t work if their children aren’t cared for. Investments in the childcare sector through the Build Back Better Act, including making care more affordable for working families and increasing pay for the workers providing this vital service, are important next steps.

The Department of Labor is committed to tracking the unique employment situation of women, women of color, and mothers, as this data will be necessary to ensure an equitable recovery to help us build back a better, stronger economy that works for everyone.

Janelle Jones is the chief economist of the U.S. Department of Labor. Wendy Chun-Hoon is the director of the Women’s Bureau. Follow the Women’s Bureau on Twitter at @WB_DOL.

| Black men | -2.4% |

| Black women | -5.3% |

| Hispanic men | -0.7% |

| Hispanic women | -3.9% |

| White men | -2.7% |

| White women | -3.6% |

Note: Seasonally adjusted employment of women and men ages 20 and older. Estimates for Asian women and men not available.

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Population Survey

Employment in Child Day Care Service (in thousands)

| February 2020 | 1046.5 |

| March 2020 | 1012.9 |

| April 2020 | 673.2 |

| May 2020 | 704.5 |

| June 2020 | 789.8 |

| July 2020 | 828.4 |

| August 2020 | 845.6 |

| September 2020 | 863.8 |

| October 2020 | 871.0 |

| November 2020 | 870.1 |

| December 2021 | 873.5 |

| January 2021 | 866.6 |

| February 2021 | 879.8 |

| March 2021 | 882.3 |

| April 2021 | 893.7 |

| May 2021 | 906.0 |

| June 2021 | 930.0 |

| July 2021 | 925.4 |

| August 2021 | 920.0 |

| September 2021 | 940.4 |

| October 2021 | 941.1 |

Source: Bureau of Labor Statistics, Current Employment Statistics

Note: Seasonally adjusted employment.

U.S. Department of Labor Blog

U.S. Department of Labor Blog